The 1897 archaeological report, by British archeologist J.E. Quibell and F.W. Green, piqued my interest, especially their find in the Temple of Horus at Hierakonpolis, King Narmer city. The discovery unfolded a number of questions from this Early Dynastic Period – 3150-2686BC, given the unusual implements found in the Temple; one in particular.

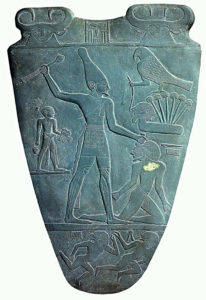

Quibell and Green found the Narmer Palette, a shield-shaped ceremonial flat dark-gray siltstone, carved from a single piece, 25in/63cm high. Both sides are finely carved in raised relief. Unsurprisingly it is also known as the Great Hierakonpolis Palette.

“The next step after capture of an adversary or challenger, was decapitation. There is no reason to believe that the outcome of capture would have been different in Egypt.”

For the purpose of this narrative, the focus will be on the central figure of the front face of the Palette, at right below. I will not address the historic significance of the allegory shown, but its affinity with a similar display of power in Mesoamerica, over 3000 years later. The allegorical scene on the Pallet triggered a number of questions.

The Palette, front and back, show conventional Egyptian representations of important actual and mythological figures, carved on stone, painted on ceramic or carved and painted on wood. As a rule, the representations adhere to a strict artistic tradition, where the position of figures must follow specific criteria dictated by the Pharaoh himself and high court priests.

The emblematic convention display figures of human or animal, gods and deities and secular or sacred implements. The individual is generally portrayed in profile with striding legs, but the torso seen as from the front. The canon of the body proportion is based on the “fist” measured across the knuckles, with 18 fists from the ground to the hairline on the forehead.

Both conventions remained in use until at least the conquest by Alexander the Great, some 3000 years later.

The larger picture on the front face of the Palette, right, depicts Pharaoh Narmer wielding a mace, wearing the White Crown of Egypt. To the right is a kneeling prisoner, who is about to be struck by the king. Other elements of the composition are not relevant to our analysis, nor is the back of the palette.

Narmer holds the prisoner’s tuft of hair at the front or top of the head, with his left hand. He brandishes a mace in his right hand and extended arm, about to strike the captive. The position of the arms and function of the hands, together with the captive’s hair tuft held by the king, are central elements in our correlation.

Fast forward to 740AD and the great Maya site of the Classic, Bonampak, in the State of Chiapas, Mexico. In the Temple of the Paintings (T1), of this small but significant city and its unique wall paintings, in Temple.1/Room.3/Lintel.3 show a limestone tablet that depicts a very similar scene as that of Hierakonpolis, over 3000 years earlier.

The scene celebrates the military victory by an earlier Lord, Jaguar Knotted-eye, shown holding his lance at the point of killing his captive he holds by the tuft of hair with his left hand. The position of both figures, their hands and arms, as well as the moment of capture, are closely similar

Such scenes are common throughout the stone and ceramic record of the Americas.The Aztecs used the same symbolism in depicting their victors and vanquished. The Cuauhxicalli round monolith below, shows the same scenes, within an identical context as described above.

The next step after capture of an adversary or challenger, was decapitation. There is no reason to believe that the outcome of capture would have been different in Egypt.

We know that representations of life and events at court represented in stone, ceramics, metals, wood or fabric answered strict criteria, established by and for the ruling elite. Both exoteric and esoteric symbolisms were built in to convey a clear message to the members of the group, as well as to those foreign to it. Symbolism however, was aimed at segments of the group educated in the use of language or other forms of communication.

The question therefore is not so much if symbolism migrated from one place to another; we know that there is no doubt that it did between North and South America. What is more doubtful however, is an East-West migration at the time of Narmer, 3000BC, an immense gap in time and space.

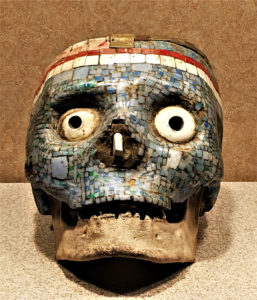

The archaeological record evidence the fact that the most common prize in battle or sacrifices, through time and cultures worldwide, is the male human head.

May be observed in both the Old and New World cases, their very close pictographic architecture which raises the question of a common denominator. Need be noted that the tuft of hair held by the figures in all representations, are from either the front or top of the head, never from the back.

The denominator is not the depicted scene in and of itself, that is the exoteric part of the message. It may only lie in the esoteric part: the positions of the bodies, arms, hands and taking of the tuft of hair by the captor. The ultimate point of the message it seems is the last, the tuft of hair and its extension, the head.

The archaeological record evidence the fact that the most common prize in battle or sacrifices, through time and cultures worldwide, is the male human head. Live ritual capture and ulterior decapitation was the mark of a great warrior and central to secular and religious rituals.

The obvious answer to gender election is that most heads were severed during or after battles. Of note is the fact that not all heads, during such encounter were preserved, only those of noted individuals that, in the eyes of the adversary, carried a certain significance while other individuals of that group did not, such as of a member of the nobility, governing body or that of a war chief.

Aside from violence inherent to combat and ritual killing then, why was the head preserved for, and frequently adorned with mosaic, paint or other ornament? In other words, what was preserved of the owner of the head or, rather, what part of the stream of life of the opponent had to be controlled?

An aspect of this tradition points to an important link with ancestor worship. An ancestor that directly, or through family lineage, carried a certain power in the community, will have his skull preserved as it was believed to hold the “mana” or power from the ancestor lineage. Note that a skull of the same family was not necessarily preserved, unless it carried power of the deceased to the descendants.

By keeping the skull and venerating it, part of the “mana” power was believed to transfer to the worshipper and his clan. In Austronesian languages mana means “power” or “prestige”, and is grounded in super-natural power.

This belief is a universal construct of great antiquity. The continuum of the life-death cycle migrated from the Old to the New World over the Bering iced land bridge during the upper Paleolithic. It was disseminated throughout the Americas, where it is still practiced (minus decapitation) to this day. Is the riddle solved then? Well, not really, there is much more to it and will require further research; so, stay tuned.

Bibliography

Narmer Palette Bibliography – Stan Hendrixx, 2017

Early Dynastic Egypt – Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, 1995

Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians – Bob Brier, 1999

Bonampak – Martha Ilia Nájera Coronado, 1991

Maya Cosmos – D. Freidel, L. Schele, J. Parker, 1993